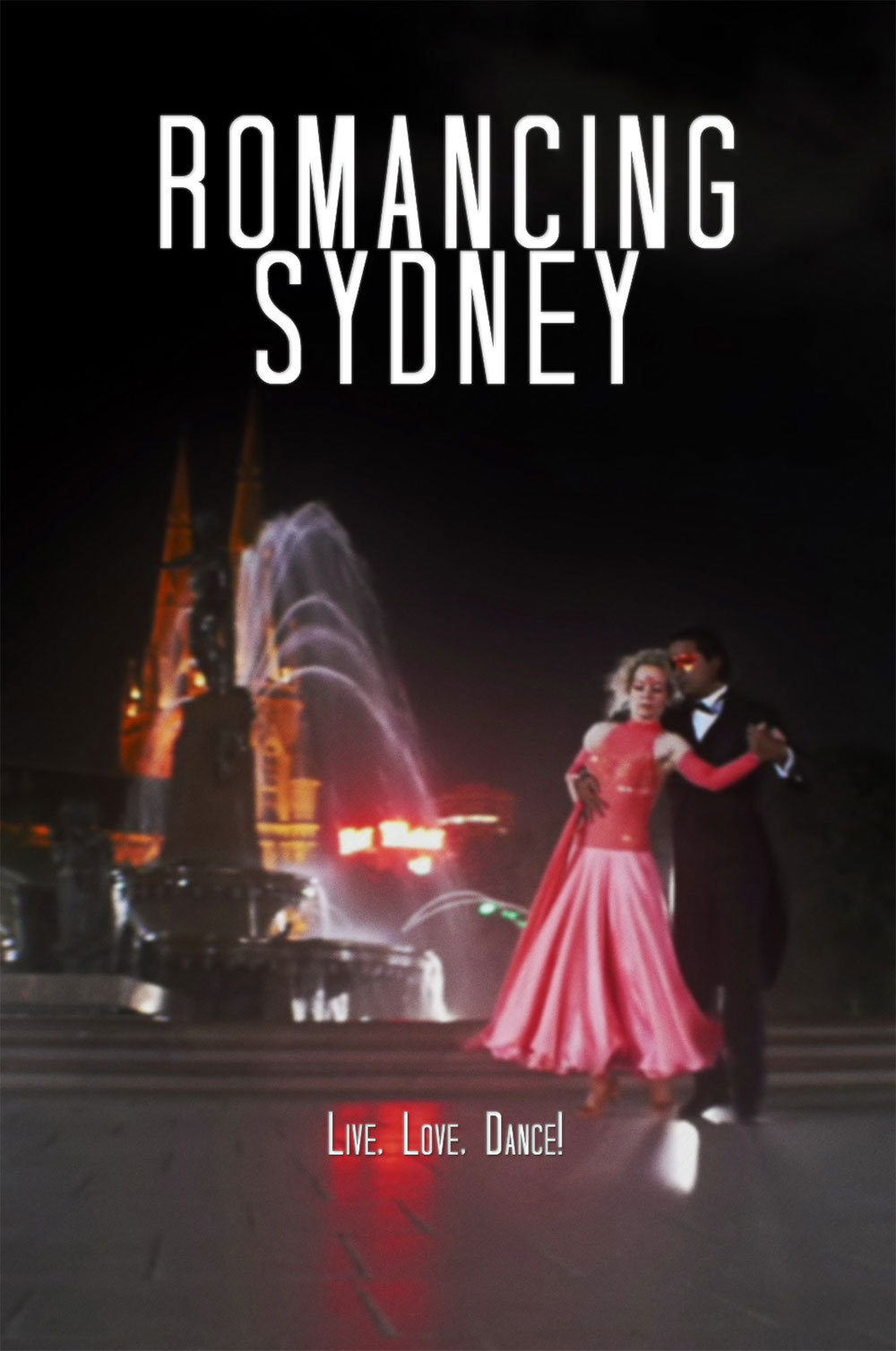

Anmol Mishra’s Romancing Sydney arrives as a curious, sprawling, and deeply earnest entry into the 2025 independent film circuit. In an era where the mid-budget theatrical release has all but vanished, seeing a work that feels as though it were born from a fever dream of old Hollywood musicals and the gritty, unwashed reality of modern immigrant life in Australia is genuinely startling. While the film markets itself as a romantic comedy, that label feels like a strategic misnomer designed for streaming algorithms. In truth, Romancing Sydney is an experimental visual essay—a “dance-fueled” exploration of human connection that treats its namesake city not just as a backdrop, but as a central, demanding, and often indifferent character. The trailer itself offers just a montage, with music and dance, with no dialogue.

The film follows six interconnected lives as they navigate the messy, often non-linear path of modern love. It is a narrative defined by high ambitions and painfully humble resources. While it occasionally stumbles under the weight of its own narrative complexity and palpable technical limitations, its undeniable heart and stunning choreography elevate it into a noteworthy, if polarized, piece of independent Australian cinema.

A Tapestry of Intertwined Lives: The Narrative Friction

Mishra opts for a multi-strand structure reminiscent of Love Actually, Magnolia, or the Cities of Love anthology series (Paris, je t’aime, etc.). The intent is clear: to weave together three distinct romantic arcs that represent different facets of the contemporary Sydney experience—the aging local, the desperate migrant, and the marginalized youth. However, the execution of these strands is where the film finds its greatest inconsistency, revealing a script that often struggles to give its characters the breath they need to feel like three-dimensional beings.

The Anchors: George and Lilli

The most successful and emotionally resonant arc belongs to George (Peter Hayes) and Lilli (Gabrielle Chan). Their dynamic is the film’s “gravity.” George is a character archetype we’ve seen before—the aging “ladies’ man” who uses a facade of vintage bravado as a shield against the creeping irrelevance of old age. But Hayes imbues him with a weary, quiet desperation that feels startlingly real. He secretly pines for Lilli, his boss at a dusty, claustrophobic antique shop. Lilli, played with sharp-tongued brilliance by Chan, is the film’s grounded center. She is the “feisty” foil to George’s posturing, yet Chan allows us to see the cracks in her armor—the exhaustion of keeping a small business alive in an increasingly digital world.

Their subplot provides the film’s core tension. Unlike the younger couples, whose problems feel ephemeral and tied to the “now,” George and Lilli’s chemistry is built on years of shared silence, the hum of fluorescent lights, and the physical weight of the antiques surrounding them. There is a “lived-in” quality to their scenes that the rest of the film lacks. However, this success highlights a major structural flaw: despite being the emotional heartbeat of the movie, they are the only couple denied a major dance sequence.

As a viewer, one can’t help but feel that a fantasy sequence involving these two—perhaps a slow, melancholic waltz through the shop as the furniture comes to life—would have lifted the film into a higher echelon of storytelling. Instead, their saga feels somewhat incomplete, as if the director ran out of film or courage before their resolution could be fully realized. Furthermore, the film keeps them trapped within the four walls of the shop. Had Mishra taken George and Lilli out into the Sydney streets—perhaps a dialogue scene on the steps of the State Library or a quiet moment in Hyde Park—it would have broken the visual monotony and reinforced their connection to the city they’ve inhabited for decades. With this said, the multiple bright lights and the bright colors in the antique shop make for an interesting experience, albeit overdone.

© Romancing Sydney (2025)

The Cynical Meet-Cute: Elisa and Sachin

In stark contrast stands the story of Elisa (Susanne Richter) and Sachin (Anmol Mishra himself). Elisa is a German dancer struggling with the bureaucratic nightmare of Australian visa issues and the looming threat of homelessness—a reality for many in Sydney’s current housing crisis. She meets Sachin, a naive employee at the same antique shop, in a “meet-cute” born from mutual misfortune.

While the film attempts to frame this as a blossoming romance, it feels curiously hollow. Unlike the sweetness found in George and Lilli, this pairing is tinged with a cynicism that feels accidental rather than intentional. Their evolution doesn’t feel natural; rather, it feels as though the characters are being moved across a chessboard to justify the next dance sequence. Sachin and Elisa often feel like sketches rather than portraits. They appear more as conduits for the film’s visual ambitions—the “reason” to have a dance number—than as people we are meant to root for. The audience is left feeling that if Elisa didn’t need a visa and Sachin didn’t need a purpose, they wouldn’t have two words to say to one another.

The Missed Opportunity: Zac and Alex

The third arc involves Zac and Alex, a couple whose bond is forged through the shared language of dance and gymnastics. Their story carries the most significant dramatic weight on paper—dealing with the pressure of Zac coming out to his traditional parents before their impending wedding. This is the most compelling conflict in the film, yet in practice, it is the least developed.

The film shies away from the grit of their domestic struggle, opting instead to let their bodies do the talking. While the film displays their athleticism, the lack of narrative development makes their eventually conflict feel unearned. We see them dance their emotions (more so for Alex than for Zac), but we rarely hear them speak it. This creates a disconnect; we admire the performance, but we aren’t invited into the relationship.

Movement as Language: The Film’s Saving Grace

Where Romancing Sydney truly finds its voice is in its movement. Structured around six intricate routines, the film allows dance to take over where the screenplay falters. In these moments, the clunky dialogue and uneven pacing vanish, replaced by a “visual velvet” that is genuinely arresting.

Director Mishra shoots these sequences with a dynamic purpose that far exceeds the quality of the static, dialogue-heavy scenes. He utilizes the geography of Sydney—specifically its fountains and its colonial architecture—to create “fantasy ballrooms” out of thin air. In one particularly poetic moment, iconic Sydney landmarks are projected onto the dancers’ bodies. It’s a literal manifestation of the film’s theme: the way a city marks its inhabitants, and the way those inhabitants, through their pain and joy, give the city its soul.

However, there is a missed opportunity here as well. While the dance numbers are beautiful, they often feel “quarantined” from the rest of the movie. More dialogue scenes could have been filmed outdoors to bridge the gap between the grounded reality of the antique store and the elevated reality of the dance. Seeing George and Lilli argue in the harsh daylight of Circular Quay would have added a layer of realism that the shop’s stagnant air couldn’t provide.

The soundtrack, a blend of original ballads and re-imagined classics, works in tandem with the choreography to create an atmospheric immersion. For minutes at a time, the film becomes a silent movie, conveying more through a hand gesture or a synchronized leap than any of the “meh” dialogue could hope to achieve.

© Romancing Sydney (2025)

Technical Ambition vs. Reality: The Indie Struggle

A 3.5-star rating is a “sympathetic” score. It recognizes the Herculean effort required to make a feature film on a shoestring budget in 2025 while acknowledging that the viewer will need to overlook significant flaws.

Audiences empathize with characters through relatability—shared flaws, human experiences, and relatable goals. We need emotional vulnerability; we need to see the fear, the grief, and the joy behind the eyes. By revealing a character’s inner world through confession or action, creators bridge the gap between the audience and the fictional person. Romancing Sydney often fails to do this. Because the script and the dialogue are underbaked, the audience is frequently left unimpressed by the struggles on screen. We feel for the characters because they are in bad situations, but we don’t feel with them because we don’t truly know them.

The technical shortcomings are equally distracting. The sound design is inconsistent, though the background score adds to the vintage Hollywood vibe. The lighting, too, is basic. In the antique shop, it often feels flat and functional, failing to match the vibrant, saturated cinematography of the outdoor dance numbers. This creates a visual “whiplash” that reminds the viewer they are watching a low-budget production.

Furthermore, the pacing suffers from uneven rhythms. The film oscillates between the kinetic energy of the dance numbers and the sluggishness of the narrative scenes. Because the subplot of George and Lilli is so much stronger than the others, the audience finds themselves waiting for the film to return to the shop, creating a disjointed viewing experience. Even with these two, some outdoor dialogue scenes would have helped the monotony of the shop’s saturated colorful palette. The film feels like a collection of beautiful short films that haven’t quite been stitched together into a seamless whole.

The Cultural Context of 2025

In the landscape of 2025 cinema, where AI-generated content and hyper-polished, soul-less studio products dominate our feeds, there is something deeply refreshing about Romancing Sydney’s rough edges. It is a “handcrafted” film. You can feel the director’s fingerprints—and his sweat—on every frame. Its willingness to take creative risks shows a level of artistic bravery that is often polished out of larger productions.

It captures a specific “Sydney mood”—the feeling of being surrounded by millions of people yet remaining fundamentally alone. It explores the immigrant experience not through political lectures, but through the universal language of physical movement and the quiet, soul-crushing indignity of a visa application.

Final Verdict

Romancing Sydney is a “festival darling” that rewards the patient, empathetic viewer. It is not a movie for everyone. Those looking for a slick, fast-paced romantic comedy will likely be frustrated by its technical lapses, its “meh” dialogue, and its narrative gaps. However, for those who appreciate experimental indie efforts and the sheer artistry of dance, it is a uniquely well-crafted piece of cinema.

The film proves that heart can matter more than spectacle. While the story of Sachin and Elisa may feel superficial, and the story of Zac and Alex may feel truncated, the overarching “feeling” of the film remains long after the credits roll. It is a flawed, beautiful, frustrating, and ultimately joyful experience. It is a film that reminds us that even in a city as vast and indifferent as Sydney, there is always room for a little bit of romance—provided you’re willing to dance for it.

Where to Watch:

Romancing Sydney is currently available for streaming on Amazon Video, Apple TV, and Google Movies. To truly appreciate the choreography, it is recommended to watch on the largest screen available.