This article is a takedown of Conceptual Art while praising its functional twin, Conceptual Work. Don’t be afraid, it will still be Conceptual Art, but we’ll have much higher expectations. In today’s art world ridden with charlatans, it seems a good idea to unpack concepts to learn what’s gold, what’s trash. Conceptual art obviously means when an idea is ideally the work of art. Sol Lewitt claimed the conceptual mantle when he wrote that. But dictionaries say an idea isn’t art, it’s science; “a systematic enterprise that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe”. Having an idea isn’t work. Having an idea means to be aware of content that originated in the depths of the unconscious mind and that rose until it came to consciousness; “that idea just dropped into my head”. Having an idea is thrilling but needs a reality check… for an idea could be a brilliant mistake. Sol Lewitt’s idea is debunked since art is always an achievement, accomplishments take effort, a “work” of art means work. Asking for a friend.

What’s bad news is some in the conceptual world discarded logic and common sense in favor of shock tactics. That’s how Maurizio Cattelan’s banana duct-taped to a wall sold for $125k, how Martin Creed’s “Lights Going On and Off” sold for six figures. Creed’s work consisted of a sheet of paper instructing the museum to switch the gallery lights off, then back on, for the length of the show. There’s a Canadian artist who works with garbage, but each piece contains an outrageously expensive element, convincing top museum curators that this artist must be good if he’s so expensive. The trigger is that shock of an anti-aesthetic denying traditional art. How could these works command such high prices? Conceptual art may sell to wealthy players who find the game hilarious, or to gambler playing the odds that the conceptual bubble will never burst. After all, Piero Manzoni Merda D’artista, which cost $37 a can in 1961 sold for 275,000 euros in 2016. An acquaintance’s friend bought two cans in the 1960s and opened one of them, to find it contained plaster. Much daintier for the artist to deal with, assuming no one would ever know.

We separate gems from dross through standards. Manzoni’s cans are great as fashionista history or art curiosities… but not so much as a work of art, for numerous reasons including its semiotic reading. What does the work say? A pile of trash in a museum says trash is art and art is trash. That’s dangerous if art is the canary in the cultural coal mine… equally disturbing if art influences social behavior. A urinal says art is to piss on. What kind of message is that? Is it aspiration, deconstruction, self-destruction? Creed’s lights on and off speak of a bad connection in the art world, Cattelan’s banana says that when art is anything you can get away with, the worst you can get away with is always the most effective strategy, leading to a steady degradation of the field. The term conceptual art is questioned; ideas are neither a work nor a media; they’re a thought, whereas in real time art takes work.

If anyone’s a poster boy for quality conceptual work, it’s Bruce Barber, Professor Emeritus at Media Arts/ Art History and Contemporary Studies, NSCAD University. There are some people who can make a chocolate cake using only orange peels. We call them gifted. I met Barber years ago when I documented his Toronto performance Diddly Squat. It consisted of him scraping bubble gum off the sidewalk in front of the Cameron Hotel, dressed in orange prison overalls, on the back of which were stitched the letters “artist performing 30 hours of community service. The photographs show burst of color; the deep blue paint in a mural by John Abrams on the Cameron’s wall, with huge ruby red lips on that blue mural blending Barber’s orange jumpsuit into Abram’s mural. All the elements click together.

1) The artist performs 30 hours of community service. Specific artist associated sites along Queen Street West in Toronto are chosen by the artist who proceeds to systematically scrape (and collect) gum patties from the pavement over a thirty hour period. 2) Queen West Squat. The artist publicly nominates a vacant building in the city as an official squat by placing the internationally recognized squat sign on the door and windows of the building. Leaflets advertising this space as such, are distributed to homeless people who the artist meets on the streets of Toronto during his 30 hours of community service. 3) Credit Identity. The artist reads out all of his credit card numbers and expiry dates in a public place.

Barber is also a writer who hobnobbed with Lucy Lippard, he’s an intellectual from whom I learned the term littoral art. Littoral is the space where the waves wash over the shore. Depending on tides, littoral space shifts between being land and sea. In art that means whatever straddles the definition between art and non-art.

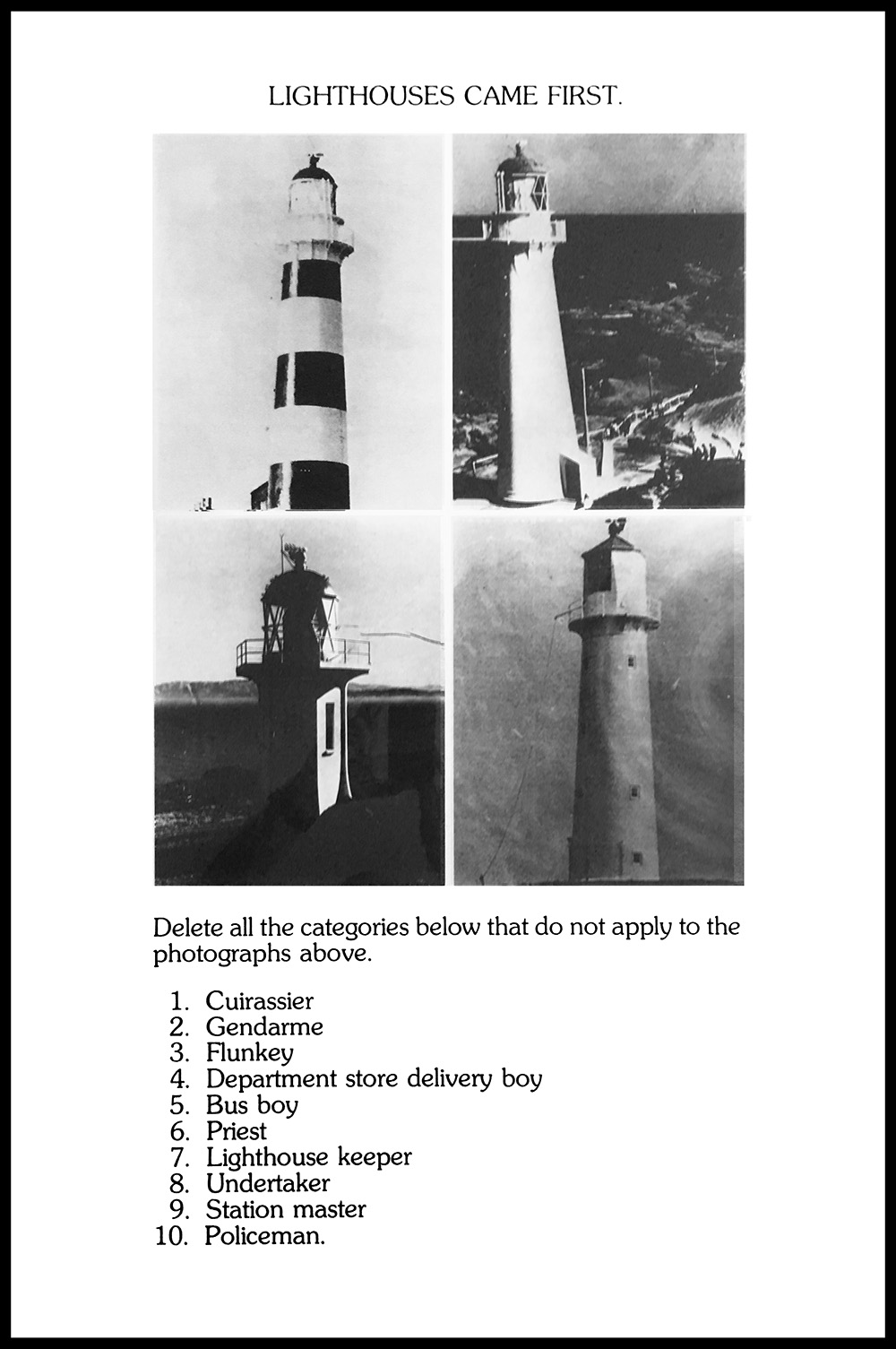

Lighthouse is obviously a conceptual work as at face value it seems nonsense, then hints you have to think to get it, but getting it opens a treasure trove of memories and their associated feelings. At first glance we find the answer to what came first, obviously, this isn’t about chickens and eggs, is it colonization, the conquest of distant lands, or is it about communication and the guiding of ships lost near the coast? Still, there’s a sexual tinge considering the phallicity of these erect lighthouses. Now remembering a cartoon of the chicken and egg in bed, the chicken, satisfied, is smoking a cigarette, but the egg looks frustrated.

The individuals in the image taken on Rangitoto Island in the gulf of Auckland City, include from left to right: Dr. Wystan Curnow art critic prof, John Lethbridge artist (now living in Australia) Bruce Barber artist, Lucy Lippard critic & curator, Mel Bochner, artist in the Some Recent American Art exhibition at the Auckland City Art Gallery, MOMA curator not identified. Photographer possibly Pamela Allen.

Underneath it says “now we know the answer that question!” No, pass on the chicken and eggs, let’s look at the work again.

The instruction to delete all the categories that do not apply suggests clues. Only no. 7 remains, the others deleted, Look at them again, seeking those clues hinted at, but no. We’re left with the question of which came first, lighthouses or the lighthouse keeper? Logic answers… but why that question?

Jung writes of the psychology of tea cup readers forecasting one’s fortune. Often these people are remarkably close to the client’s secret wishes, because human behavior is so consistent the major questions of life remain the same. The specifics can be picked up through body language by someone empathic enough. The jumbled tea leaves presents the fortune teller with a chaotic pattern that shuts down intellect for a second, silences logical thought, allowing unconscious content to filter in, like the ideas that drops into our head. This strategy works equally well here, triggering thoughts, feelings, emotions in the viewer.

The graphics are minimalist, impeccable, and remind us of CAPTCHA, Completely Automated Public Turing test to tell Computers and Humans Apart, a program or system intended to distinguish human from machine input, typically as a way of thwarting spam and automated extraction of data from websites. The treasure trove aspect comes when Lighthouse reminds us of children’s tests in school. Because this work is so whimsical the child’s memories entwine with a feeling of fun, and all this occurs on subliminal levels, before that response pops into our head. Psychology says consciousness is often the last one to know what’s going on in the brain.