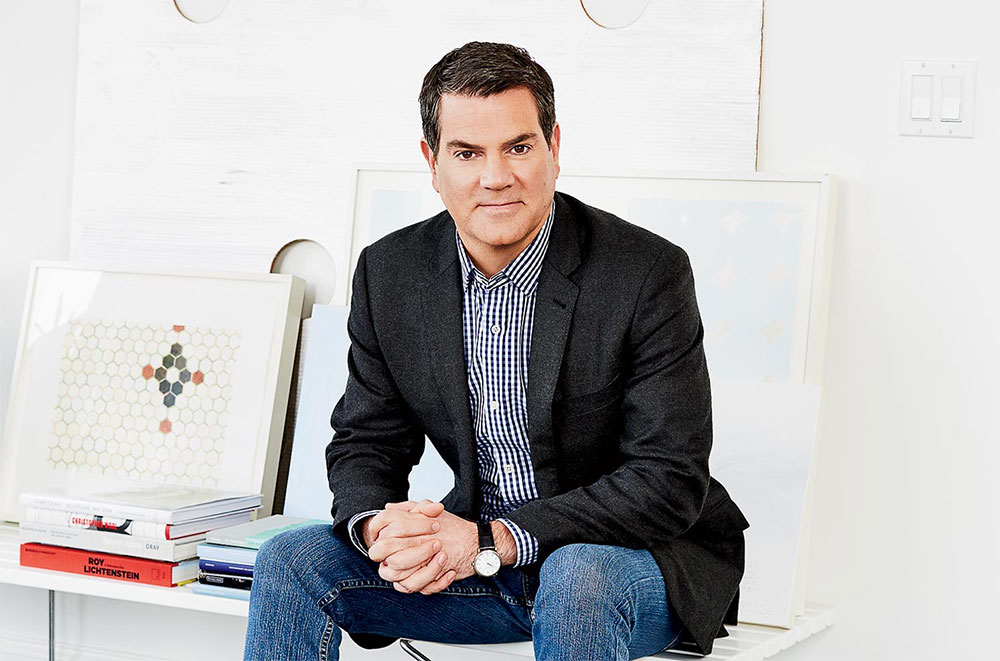

Since James Rondeau became president and director in 2016, the Art Institute of Chicago has presented exhibitions spanning centuries and continents. From Indigenous basketry to Pan-African art, from Georgia O’Keeffe’s urban experiments to portraits of Barack and Michelle Obama, the museum’s recent programming reveals both deep art-historical scholarship and expanded narratives. Rondeau enabled curators to emphasize the importance of variety and balance in the museum’s exhibition roster to achieve its mission.

Pan-Africanism as Visual Culture

Project a Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, which opened December 15, 2024, brought together 350 objects to examine Pan-Africanism’s cultural manifestations from the 1920s to the present. Co-organized with MACBA Museu d’Art Contemporani de Barcelona, the exhibition presented Pan-Africa not as a fixed territory but as a shifting aesthetic.

The exhibition centered on three foundational movements: Garveyism, Négritude, and Quilombismo. Kerry James Marshall’s Africa Restored (Cheryl as Cleopatra) (2003), a wall-sculpture shaped like the African continent, anchored one gallery. David Hammons’ African American Flag (1990) appeared alongside works by Beauford Delaney, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye, and Malangatana Ngwenya. Ebony G. Patterson’s Invisible Presence: Bling Memories (2014)—50 decorated coffins on pale blue pedestals—referenced Jamaican funeral rituals while evoking collective resilience.

The show closed March 30, 2025, capping a year-long “Panafrica Across Chicago” season involving nearly a dozen organizations. The Art Institute accompanied it with complementary installations, including After the End of the World: Pictures from Panafrica, a photography exhibition exploring environmental sustainability and freedom.

O’Keeffe’s Manhattan Period

Georgia O’Keeffe: “My New Yorks,” on view June 2 through September 22, 2024, gathered approximately 100 works—including paintings, drawings, pastels, and photographs—from O’Keeffe’s urban period between 1925 and 1930. The exhibition positioned these cityscapes, long overshadowed by O’Keeffe’s Southwestern work, as integral to understanding her development.

After moving to the Shelton Hotel in 1924, then the world’s tallest residential building, O’Keeffe created what she termed “my New Yorks” from her 30th-floor vantage point. The exhibition included The Shelton with Sunspots, N.Y. (1926) from the museum’s permanent collection, which depicts the 34-story building partially shrouded by the sun’s glowing orb. Other works showed O’Keefe oscillating between sprawling views looking down onto the city and upward perspectives of newly built towers.

An untitled 1924-26 charcoal drawing offered a semi-abstracted view from the Shelton toward St. Patrick’s Cathedral’s distant spires. East River from the Shelton (1927-28) juxtaposed natural elements with industrial smokestacks.

The exhibition contextualized these urban landscapes alongside her more well-known concurrent work with shells, flowers, and Lake George scenes.

An accompanying catalog examined how these works reflect narratives of built environments and the politics of place.

Indigenous Basketry as Contemporary Art

Jeremy Frey: Woven, on view October 26, 2024, through February 10, 2025, presented a mid-career retrospective of the Passamaquoddy basketmaker’s work. Organized by the Portland Museum of Art, the exhibition included more than 50 baskets crafted over two decades from ash wood, sweetgrass, birch bark, and porcupine quillwork.

One of the centerpieces, Nearly Monochrome, acquired by the Art Institute in 2022, stands over 31 inches tall. Frey, a seventh-generation basketmaker, creates vessels that blend traditional Wabanaki techniques with contemporary formal experimentation. His recent works add decorative embroidery depicting animals and landscapes using porcupine quills.

Frey won Best of Show at Santa Fe Indian Market in 2011, becoming the first basketmaker to earn that honor in the event’s 90-year history. He repeated the achievement at the Heard Museum Guild Fair and Market in Phoenix in 2015.

Theresa Secord, a Penobscot basketmaker and founding director of the Maine Indian Basketmakers Alliance, served as cultural consultant. The accompanying Rizzoli catalog includes essays examining how Frey’s practice registers ecological knowledge, time, and climate change’s impact on materials like black ash.

The Obama Portraits

In summer 2021, the Art Institute hosted The Obama Portraits, bringing Kehinde Wiley’s painting of President Barack Obama and Amy Sherald’s portrait of former First Lady Michelle Obama to Chicago as the first stop on a five-city national tour.

Calling the exhibition “a narrative homecoming,” Rondeau cited the couple’s ties to the city and the museum. “There’s a very special relationship between not only the City of Chicago, but between our museum and the president and the first lady,” he said. “We’re still, especially in Chicago, very much in the present tense with the president and Mrs. Obama.”

Michelle Obama visited the museum frequently while growing up on the South Side, and the Art Institute was the site of the couple’s first date. “It’s now almost mythical that the president and the first lady had their first date here,” Rondeau said.

The exhibition broke daily attendance records for the museum. “The Obamas and the museum help define Chicago for people outside Chicago,” Rondeau told The Washington Post at the time.

The paintings tell a story of “a president and a first lady, a narrative of all the firsts they represent,” he continued. “But seeing them on the wall together, they are perhaps a little more like Michelle and Barack Obama. They carry all of the historical precedents, and they carry some of their humanity.”

Rondeau also described the portraits as uniquely accessible despite their subjects’ stature. “These are obviously portraits of service, they’re portraits of power, they’re portraits, let’s be honest, of international, really global, celebrities of the highest order,” he said. “All that iconicity around power and celebrity is there, but also they’re incredibly accessible.”

Free admission for Illinois residents during the first week and throughout the run helped ensure access for Chicago communities with deep connections to the Obamas’ legacy.

Barbara Kruger: Pushing Boundaries

Later in 2021, the Art Institute mounted Thinking of You. I Mean Me. I Mean You, the first major museum survey of Barbara Kruger’s work in the United States since 1999. The exhibition encompassed four decades of the artist’s practice and later traveled to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

The show was deliberately structured as what Kruger called an “anti-retrospective,” eschewing traditional chronological presentation. Instead, the artist reworked and reimagined earlier works for the present moment: 40 of the nearly 80 works in the exhibition were made or remade specifically for the show.

“Kruger’s enduring subject is power as product, both in terms of the anonymous collective machinations of social control and its accumulation and abuse by singular worthies,” Rondeau said.

The exhibition activated spaces throughout the Art Institute, with large-scale vinyl room wraps, multichannel videos, and installations extending from the Regenstein Galleries to the building’s exterior façades. Kruger’s work also spilled into the city on billboards, buses, and storefronts along Michigan Avenue.

For Rondeau, the exhibition held personal significance. “Barbara’s work changed my life,” he told the Chicago Sun-Times. “As a student, as a young curator, as a citizen, frankly, I learned so much from it and have been shaped by her work.”

He described Kruger as the first artist who taught him “that art can be an integral part, if not even an engine, for urgent public discourse.”

“In this case, Barbara herself is the engine of a critical reappraisal of her own,” he continued. “Migrating those messages into the present tense, that’s what I think is absolutely amazing. And I don’t know that anyone has ever actually done this: just blow up the model of the retrospective and do that reappraisal yourself and migrate 1985 into 2021.”

Additional Exhibitions

The museum’s 2020-2025 schedule also included Bisa Butler: Portraits (2020); The Language of Beauty in African Art (2022); Salvador Dalí: The Image Disappears (2023); Remedios Varo: Science Fictions (2023); and Radical Clay: Contemporary Women Artists from Japan (2023). In 2025, Frida Kahlo’s Month in Paris: A Friendship with Mary Reynolds examined Kahlo’s 1939 visit and relationship with Reynolds.

These exhibitions reflect curatorial choices that balance the museum’s historical strengths with efforts to broaden representation across cultures, time periods, and artistic practices. They draw on both the permanent collection and loans, often accompanied by scholarly catalogs that advance research in their respective fields.

The programming also builds on the museum’s growing contemporary collection, which builds on the historic 2015 acquisition of the Edlis-Neeson Collection: 44 contemporary works valued at approximately $400 million that Rondeau, then curator of contemporary art, called “a group of objects that no amount of money today could replicate given the current marketplace.”

The Art Institute’s programming under Rondeau has included exhibitions that collapse boundaries between established and emerging canons, with choices that suggest an institution increasingly comfortable balancing its encyclopedic collection with contemporary aesthetics.