A new scientific study examining Earth’s climate during an era of extreme ancient warmth has revealed insights that may foreshadow how rainfall patterns could change as the modern world continues to warm. Researchers reconstructed precipitation patterns during the Paleogene Period, 66 to 48 million years ago, when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were significantly higher than today, to better understand how rainfall responds under high-temperature conditions.

Scientists from the University of Utah and the Colorado School of Mines used geological “proxies” such as plant fossils, soil chemistry, and river deposits to infer how rainfall behaved during this period. Their findings challenge a long-held assumption that a warmer world simply makes wet regions wetter and dry regions drier. Instead, rainfall became much less predictable, with long intervals of dryness punctuated by episodes of intense precipitation.

The study suggests that under extreme warming, mid-latitude and continental interior regions tended toward drier conditions overall, even as polar and tropical regions experienced wetter climates. This irregular pattern—with infrequent but heavy rainfall separated by extended dry spells—indicates that the timing and consistency of rain events may change in ways that are not captured by simply measuring average annual rainfall amounts.

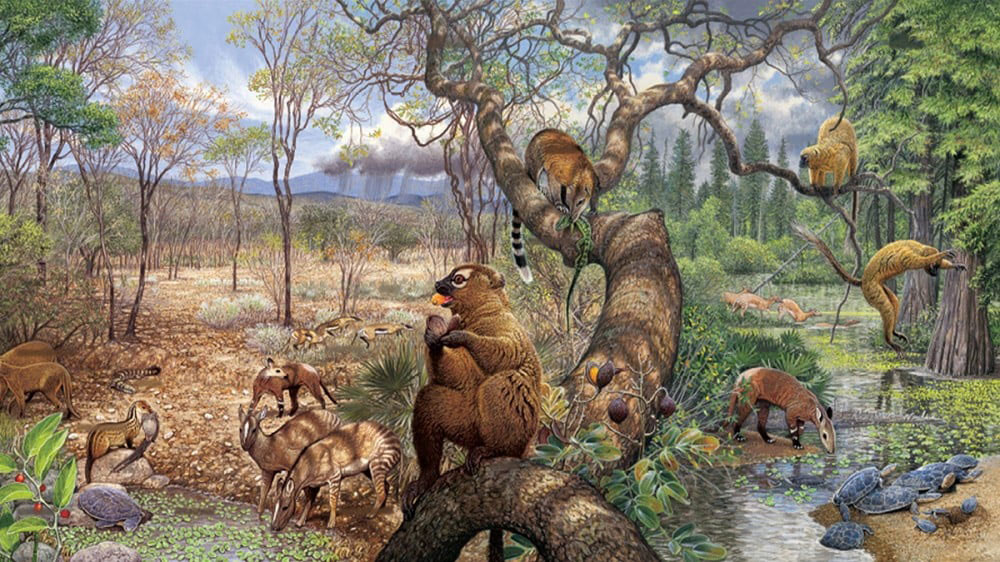

Utah’s Claron Formation, which produced the famed hoodoos at Bryce Canyon National Park, was deposited in a system of freshwater lakes between 50 and 60 million years ago during the Paleogene Period, when Earth was much hotter than it is now. © Brian Maffly

According to the research team, these results have important implications for understanding future water resources, flood hazards, and drought risk in a warming world. If rainfall becomes more episodic and more extreme, communities may face greater challenges in water management and agricultural planning, even in areas that experience no significant change in total annual precipitation.

The study, published recently in Nature Geoscience, underscores that ancient climate behavior can provide valuable context for how the Earth system responds to elevated temperatures, offering a deeper understanding of possible future climate outcomes that extend beyond contemporary observations.

Overall, the research highlights that the nature of rainfall variability—not just the quantity—will be a crucial factor as nations prepare for the impacts of 21st-century climate change.