When American Airlines Flight 77 crashed into the Pentagon at approximately 9:37 a.m. on Sept. 11, 2001, Cassandra Johnson said she had barely noticed.

Johnson now serves as the associate deputy general counsel for the Office of the Army General Counsel. In 2001, she worked as a civilian within the Defense Department’s legal community as well. On the morning of Sept. 11, she was headed into a 9 a.m. meeting and her office’s secretary let her and others know that an aircraft had hit one of the towers at the World Trade Center in New York City.

“We all looked at each other and said, was it cloudy? Was it some kind of pilot error? We just didn’t know how to react and we just continued with our meeting,” Johnson said today during an online forum hosted by the Defense Department which allowed college students to hear the stories of survivors of the 9/11 Pentagon attacks.

Johnson’s meeting was interrupted twice by somebody coming into the room and whispering something into the ear of her supervisor. Soon after the meeting was dismissed. As she walked out of the office, the television showed President Bush’s visit to Emma E. Booker Elementary School in Sarasota, Florida, where he had just been informed about the planes crashing into the World Trade Center buildings.

Back at her desk, Johnson said she returned to business as usual.

Smoke and flames rise from the Pentagon as firefighters continue to work to put out the flames. A plane struck the building Sept. 11, 2001. Witnesses said evacuation of the building was calm and orderly. Hundreds of military and civilian workers volunteered to help local medics. © Jim Garamone, DOD

“I continued back to my desk and started returning some phone calls,” she said. “And I didn’t feel the building shake or anything like that — but I did hear a very light, like a pop almost. And that was about it.”

Shortly after, she said, she learned that pop would change everything.

“The next thing I know, our executive officer comes by very calmly and says ‘Can you all just pick up your belongings, your purses, whatever, just leave the building. Let’s leave quietly.’ I remember putting my hands down on the desk saying I’ve got nothing to worry about, I’m in the Pentagon. I’m safe here.”

Outside the building, she learned quickly that she wasn’t safe — nobody was.

“I saw this big bellow of smoke — I had no idea what that was,” she said. “We proceeded very calmly, 25,000 people, if you can imagine, just emptying out. We came out into what is the south parking lot. At that moment, I know I went into shock. What I saw was, the only way I could describe it was when you hear people talk about an out-of-body experience.”

The nearby highway, she said, was stopped — like a parking lot. Police cars and firetrucks were everywhere, and the morning sky was filled with smoke.

Johnson and her co-workers heard from a police officer who told them to move away from the building because there was another hijacked aircraft in the air that could cause even more damage. The coworkers moved to nearby Pentagon City, a commercial district on the other side of the highway.

While Johnson made it home safe that night, she learned that a friend and mentor of hers, Ernest Willcher, had been killed in the attack. She said Willcher will be honored and remembered Sept. 10 at a ceremony in the general counsel’s office at the Pentagon.

Going Back

Robert Hogue, now serves as the acting assistant secretary of the Navy for Manpower and Reserve Affairs. In 2001, he was a military officer who served as the deputy counsel for the commandant of the Marine Corps. That morning, he said, he had initially misinterpreted what he was seeing happen in New York City.

After the first plane struck in New York, he said he wondered how the pilot hadn’t seen the tower. Later, when he saw the second plane hit, it still didn’t immediately click for him what it all meant.

“My first thought was, wow, lucky they got that on video. Just one of those weird things, right? The camera was in the right place at the right time,” he said. “And then I realized, holy crap — that’s a second building. And then, we’re a nation at war, and we work in the National Military Command Center. Oh my God, this is D-Day.”

The plane that hit the Pentagon, Sept. 11, 2001, peeled the building’s reinforced concrete back all the way to the “B” Ring. The area outside the Pentagon became a staging area for medical and emergency personnel. © Jim Garamone, DOD

As a military officer, Hogue said it occurred to him that the Pentagon, being in the flight path for nearby Reagan National Airport, might also be a good target for terrorists. Hogue had been headed to discuss those fears with his boss when his concerns proved to be correct.

“Right when I passed the admin chief’s desk, that’s when the plane hit,” he said. “I only have a recollection of hearing a very loud grinding noise and a vibration. And then boom — the next thing I know I’m in the corner on the north side of the office. I’ve been blown from the south side, through the ceiling tiles and the lights. And I woke up on my face looking to the west wall.”

He said he could see a cloud of smoke tumbling outside the window of the office — though the reinforced office windows had stayed intact.

“As I was looking at it I realized it was actually orange and black and then the realization, that’s a fireball. Then I see my boss in the foreground, he’s on the floor. There’s a major in there trying to pick him up. And slowly as it unfolds, we realize we’ve been hit — we’ve got to get out of here.”

A fog hung in the legal office there, he said. At first he thought it might be smoke, but then realized it was a haze of jet fuel from the aircraft and was flammable. The offices beneath his own, he said, were on fire. And he realized the danger of the situation.

“We pulled and pulled and got the door open just enough to squeeze out into the hallway,” he said. “At that point, the south side of the building is in the process of collapsing.”

In the hallway, he said, a Navy chief who was standing near where there was a construction door was calling people in the direction of safety.

“He’s using ship-board fire procedures — if you can hear my voice come this way,” he said. “Now we know we’re going to live.”

But because his boss was incapacitated and he was in charge, Hogue said he had to make a leader decision that would put the wellbeing of others before his own safety.

“I said no — we are going to search these offices first,” he said. “And we did. And we found people, and we got them out from under the desks, and we made our way down the hall for the construction entrance. And more or less, when we got to the construction entrance, by my recollection, the building fell in behind us.”

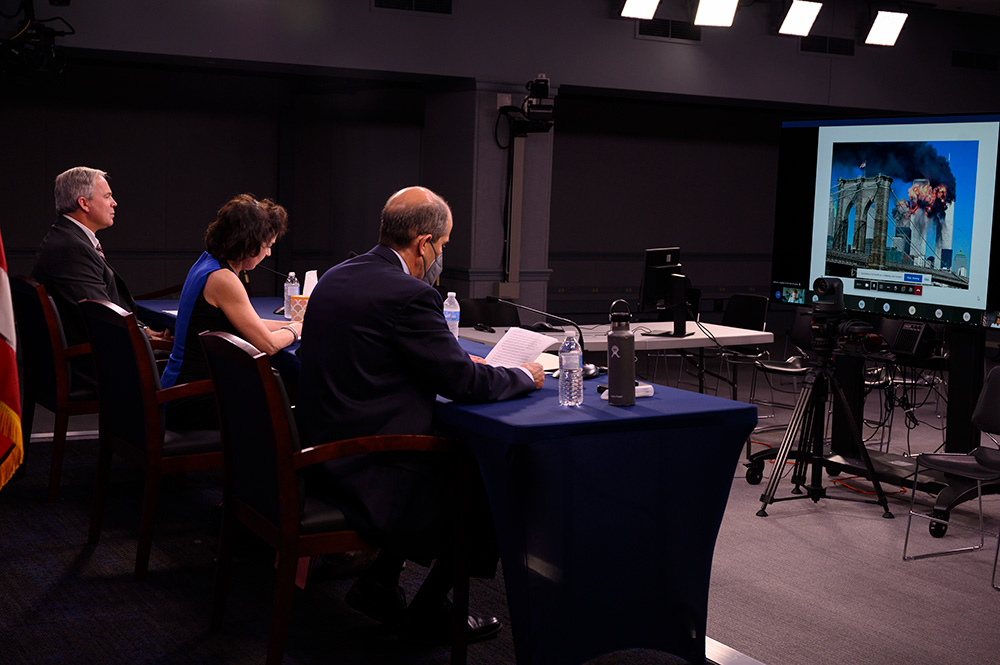

Tom Lassman, the senior historian for the Office of the Secretary of Defense, right, Cassandra Johnson, the associate deputy general counsel for the Office of the Army General Counsel and Robert D. Hogue, the acting assistant secretary of the Navy for Manpower and Reserve Affairs speak to students virtually during the Department of Defense 9/11 Commemoration University Student Panel from the Pentagon, Washington, D.C., Sept. 9, 2021. © Air Force Staff Sgt. Brittany A. Chase

Remembering Flight 93

On Sept. 11, 2001, three aircraft crashed into buildings: two in New York City, and one in Washington, D.C. But a fourth aircraft, United Airlines Flight 93, crashed into a field in Shanksville, Pennsylvania.

Johnson said she and her husband recently visited the memorial site there. She said she thinks it’s important to make an effort to remember what happened to Flight 93, because the civilians on that flight banded together to prevent another tragedy on the ground.

“I encourage you to go to Shanksville — it’s almost the forgotten sight,” she said. “If it hadn’t been for those heroes — who got that plane right into the ground and smashed into obliteration — that plane, clearly we know, was destined for Washington, D.C. I think about that every day. And that was a major sacrifice.”

Johnson said the passengers on Flight 93 had known about the Pentagon and the World Trade Center towers and made a decision to not let their own plane be used the same way.

“It was up to them to not let that happen to any other people,” she said. “When you go to Shanksville, you appreciate what they did. They took a vote on the plane — are we ready to unite and take this plane down on our terms, not theirs? And that just resonates.”